Professor Mark Brett and Dr Rachelle Gilmour

Posted on Mon 30 March 2020, by ABC Religion and Ethics

The Italian philosopher Georgio Agamben provoked widespread controversy following his recent comments on the coronavirus epidemic. He suggested that the paralysis of his country shows that people no longer believe in anything but bare life. In Australia, it would seem that our most fundamental beliefs are focused on public health and the economy. A challenge that Agamben puts to us is his stark claim: “Bare life — and the danger of losing it — is not something that unites people, but blinds and separates them.”

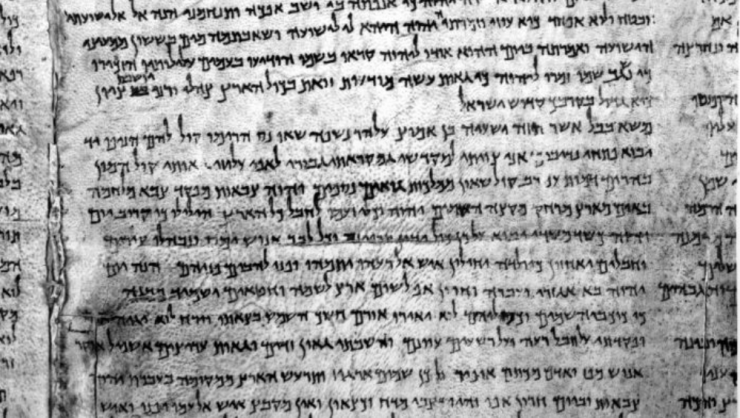

As churches adapt to the moral and legal demand not to hold services in our buildings, many priests, pastors and congregations of all types are exploring new technological resources that allow us to worship “together”: Zoom, Facebook and other types of live streaming to help us stay connected. But what theological resources do we have for this season of dislocation, physical isolation and crisis for our faith communities? The Hebrew Bible can make some contributions to this question (and not just when we note that a Hebrew word for worship is ‘avodah: an essential “service”).

In 586 BCE, the city of Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians. Some of the Judean people, mostly elites, were taken to Babylon in exile. They were separated geographically from their holy city. The rest of the people of Judah were left in their land, but separated just as effectively from their place of worship: the temple was in ruins, and their lives materially impoverished. Yet, out of these circumstances came significant portions of what we now call the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh or Old Testament.

The inner-biblical conversations at that time point to theological possibilities for our own context of crisis. One such conversation was between the book of Lamentations and Isaiah 40.

Lamentations is widely thought to have been written soon after the exile. It contains laments characterised by signs of intense grief, like weeping, mourning and groaning: “She weeps bitterly in the night with tears on her cheeks” (1:2). Other features of the book align with symptoms identified in contemporary trauma studies: the tendency to go around in circles, a resistance to explanation or even narrative continuity, the oscillation between a sense of guilt and a sense of confusion.

These laments resonate with how we might first respond to our present circumstances, with suffering experienced across our communities in many different ways. For some of us, there is also a deep grief arising from the cessation of public worship: “The roads to Zion mourn, for no one comes to the festivals; all her gates are desolate, her priests groan; her young girls grieve, and her lot is bitter” (1:4). Yet, there is a glimpse within the book of Lamentations of a response that goes beyond weeping: “lamentations” are songs sung together by the community; communities are not broken when meetings at particular sacred sites are no longer possible.

Lamentations was most likely composed towards the beginning of the exile, and Isaiah 40 was composed towards the end of the exilic period, decades later. The possibility of return was in sight for Isaiah, but far from realised. There is some debate in scholarship whether the prophetic text was written in Babylon or in Jerusalem, but what is widely agreed is that Isaiah 40 is filled with intertextual allusions to Lamentations. The text of Isaiah 40 appropriates and radically revises Lamentations’ framing of the exilic crisis. The preservation of both texts in our canon of scripture produces a dialogue, or conversation between these two perspectives.

The transformation of Lamentations in Isaiah 40 is extraordinary for a community still living in the midst of suffering. While Lamentations 1:2 cries that Jerusalem “has no one to comfort her; all her friends have dealt treacherously with her,” Isaiah 40:1-2 opens with, “Comfort, O comfort my people says your God, Speak tenderly to Jerusalem.” Lamentations 1:3 says, “Judah has gone into exile with suffering and hard servitude,” but Isaiah 40:1 responds, “she has served her term, her penalty is paid.” In Lamentations 1:4, “the roads to Zion mourn,” and in Isaiah 40:3, “A voice cries out: In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.”

This transformation of Lamentations in Isaiah 40 is not a negation of Judah’s grief and trauma, or even a replacement of it. Rather, it reflects a practice of hope that grows from experiences of trauma. Judah cried out to God — whether in accusation, desperation or a cry for mercy. Over time, it became possible to hear new theological voices. It was not an easy conversation, with voices coming from many different quarters: from Jewish communities still in Babylon, in Egypt, in Samaria, and in the ruins of Jerusalem. Imagining solidarity in worship was a huge challenge, with people dispersed over large distances.

One of the innovations at the time included a renewal of sabbath theology. This is a shift from many of the narrative books set before the exile: Joshua, Judges and Samuel don’t mention any sabbath at all, for example. (In fact, pre-exilic Isaiah 1:13 gives it very bad press, as does Amos 8:5, making clear that worship practices were obscuring social injustices).

The sabbath was a community observance of sacred time, rest from work on the seventh day. Crucially, meeting together in sacred time did not require the old insitutions of worship at particular places. “Do not go out of your place on the seventh day” (Exodus 16:29) had a new significance when people could not travel to a distant shrine. In later centuries, this principle morphed into sabbath restrictions on travel in Rabbinic tradition, but instead of focusing on restrictions, the opportunities for local observance and prayer were opened up.

One line of sabbath theology was connected to memories of the exodus (Deuteronomy 5:15), but another line grounded the sabbath in creation: according to Genesis 2:3, God sanctified the seventh day even before Israel existed. The sabbath was part of the created order and keeping sabbath became a “sign” of the bond between God and the many generations of Israel, wherever they lived. The seventh day was a cessation of labour — a stop work order — when holy time was observed “throughout your dwellings” (Leviticus 23:3). When some worship activities were eventually restored at the temples in Jerusalem and Samaria, the transformed sabbath practices continued to shape the dispersed congregations who were grounded in the universal Creator of the earth and the skies.

In the past, we have organised our faith communities by gathering in sacred space, and we have shared in one bread; now we reimagine our communities together in sacred time. We live on one earth, and at this time, the created order has sounded an alarm. We must stay home if we can, and yet our work is in many ways intensified. Health carers, supermarket workers and many others will be under unimaginable pressure — so will many people at home learning to cope with new patterns of living. Many will be grieving the loss of employment or loved ones. We are all seeking alternatives to the habitual ways of production and consumption.

In the midst of this season of work, let us revitalise our communities on the sabbath. In sacred time, we can lament together, and we can wait for the good news: “Comfort, O comfort my people … The glory of the Lord will be revealed and all people shall see it together.” Check in to a Zoom meeting with your faith community, and whether or not we lift the bread and wine together, continue to pray in the one sacred moment, “Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation.”

Rachelle Gilmour is Bromby Senior Lecturer in Old Testament at Trinity College, University of Divinity.

Mark Brett is Professor of Hebrew Bible at Whitley College, University of Divinity.

I like it. Thanks for sharing.