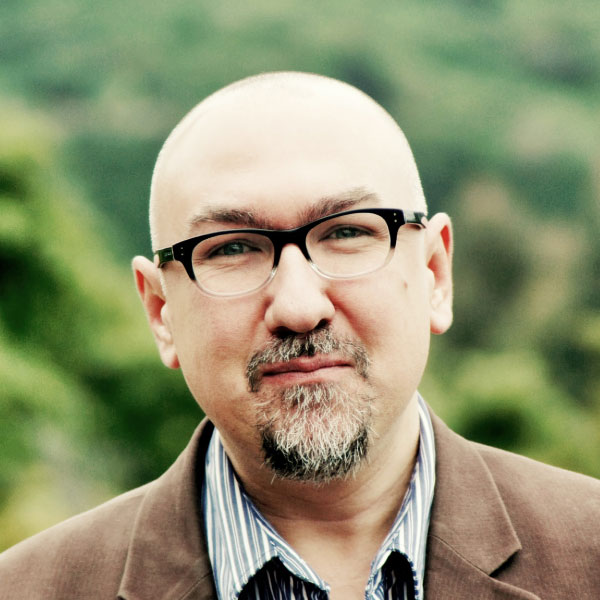

Wes Campbell is a theologian, artist, and (retired) Minister of the Word in the Uniting Church in Australia (UCA). Since completing his doctoral studies in Germany in the late 1970s, he has worked as a parish minister in Melbourne and Perth, as chaplain at the University of Melbourne, and as the Director of Justice in the Commission for Mission for the UCA’s Synod of Victoria and Tasmania.

Campbell’s work is marked by a costly commitment to peace, justice, and social responsibility. Art has always been an integral part of this work. In December 2022, Habitat Uniting Church in Melbourne hosted a large retrospective exhibition of Campbell’s paintings.

But what is the world that Wes’s paintings take for granted?

It is evident enough that the answer to that question cannot be exhausted with words, but perhaps words can assist to open up some trajectories. I want here to invite us to consider three words: attention, imagination, and participation.

Attention

The world that Wes’s work discloses is a world that can be attended to. It pays attention to what is there, refusing to forego possibilities of discovery and surprise, and celebrates mystery as an acknowledgement of the true character of things. In other words, it pays attention in ways akin to love. And love is inescapably, although not exhaustively, material. The French painter Georges Rouault would exasperate his friends by taking forever on his walks, stopping to spend time before shop windows, and picking up things from the ground to examine them. A friend once said: “Rouault thought with his hands and in the material, pondering with his eyes.”

Artists, like Wes Campbell, think in the material. They pay attention to creation — its sounds, its shapes, its colours, its peculiarities, its textures, its words — with the attention of a patient lover. And as they do so, it seems that they are taking up an invitation not only to think further about what kind of world the world would need to be in order for art to exist, or to thrive, but also what might it mean to live in a world where perception is always incomplete?

Image: Wes Campbell, “Wholeness” (Image supplied; no date given).

Wes’s work embodies the conviction that good art attends deeply to creation. It broadens our horizons, it enriches our capacity to see, it alerts us to dimensions of reality gone unnoticed and for which words are simply not enough. Artists see how things are with the world differently, but no less truthfully, than do scientists. It seems to me that if we are to walk in our world well, and justly, and with mercy, then we cannot do so without the kind of re-imagining of reality and of human society that artists promote and invite. Here the work of the arts and the work of spirit find deep confluence. The work of spirit is the work of imagination, and the work of imagination is the work of theology.

This level of attention is difficult, and risky, and patient work. It’s difficult, especially for us moderns, so wilfully distracted as we are, to sustain the kind of attention to creation that enlarges us. It’s risky to tell the truth about creation, about its joys and its subterranean dislocations. And it calls for great patience because healing of that which is fractured usually takes a long time. Desmond Tutu reminded us that it all begins with truth-telling, apart from which human relationships and human communities have no future:

Forgiving and being reconciled are not about pretending that things are other than they are. It is not patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the pain, the degradation, the truth. It could even sometimes make things worse. It is a risky undertaking but in the end it is worthwhile, because in the end dealing with the real situation helps to bring real healing. Spurious reconciliation can bring only spurious healing.

Wes’s art is alert to, and invites us stay awake to, this twin reality. It does not shy away from the risky boundaries where hope is threatened, sustained, lost, and birthed. It, therefore, embraces the tragic and the ugly, as well as joy and beauty. Whether his subject matter is the human condition, or explicitly religious stories (such as the nativity or the transfiguration), or the Earth itself, Wes’s work is replete with this kind of fidelity to the contradictions that mark our lived experience. It is, in other words, concerned to bear witness to the truth of human existence — a reminder that we live as fragile bodies marked for mortality.

Imagination

This fidelity to things the marks Wes Campbell’s work relates closely to the gift of imagination. Those, like Wes, who have devoted their lives to work as healers — whether the focus be the human body or a garden or a city or a mind or a faith community or a university — recognise that such work calls not only for reservoirs of knowledge and skills in human relationships and in exegeting human cultures, but also skills in freeing and enticing the human imagination.

Imagination is also indispensable for doing Christian theology, because it takes an awful lot of it to believe almost anything that the Christian faith holds as important. What, for example, is the promise of resurrection — a promise so prevalent in Wes’s work — if not an invitation to imagine that things might be otherwise? This is why imagination is so subversive, so threatening to those who are invested in propping up current arrangements. As Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her essay “A War Without End”:

The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.

Of course, in a world burdened by floods and wars and nuclear power and narcissistic leaders and unbridled capitalism and homelessness and food shortages and anthropogenic climate change and global pandemics and threatened democratic systems, one might be tempted to think that art is a luxury we can ill afford to devote time to. This is not the time to paint; it’s the time to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

But we’ve been here before. In the aftermath of the Second World War, for example, the German philosopher and social critic Theodor Adorno raised the question of whether our emotional responses to magnitudinous horrors ought to outweigh all our attempts to explain them. It was this query too that led Adorno to state famously that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”.

Such a view represents a major paradigm shift in our understanding of reality — a shift that began at the Enlightenment and that lingers today. The story about how and why this has happened is complex, and we need not go into it here. But it is not insignificant that Adorno changed his mind. This scholar of the arts came to see that the poetics — the sounds and languages and images — in which artists traffic are precisely the signs that are indispensable if we are to direct our efforts towards futures in which human and other-than-human life flourishes. Without imagination, there can be no new reality. Without imagination, we cannot cultivate and grow into the deep mysteries of hope, which are as inscrutable as are the presence of evil and love. Without imagination, we will cease to be at all.

Image: Wes Campbell, “Transfiguration of Christ” (Image supplied; no date given).

Participation

This notion of “we” is very important to Wes Campbell. Repudiating the tribalism and demagogic rhetoric that marks so much public discourse, his work has shown a stubborn refusal to abandon the idea of a common life, however difficult and fragile cultivating such a life proves to be.

To that end, Wes’s art explores and exploits ways that human making can connect with other activities of life, sabotaging humanity’s proclivity for mastery and management. It embodies the conviction that the arts can unmoor us, disrupt the worlds we assume, facilitate our lament, and open up possibilities for futures we hardly dare imagine — futures that may be, very often despite all evidence to the contrary. This is the gift his work offers: not certainty, nor rescue, but this other kind of gift.

Hope

To these three words, we might add a fourth — namely, hope. Wes Campbell’s paintings entertain no illusions that artists can heal the Earth, at least not on their own. What artists can do, however, is to participate with others in building communities that are life-giving and life-honouring, communities that believe that ecosystems can be renewed, and that diseases, both biological and social, can be resisted. And for artists who happen to be people of religious faith, this might include a sense that such work is about participating in the healing movements of God, in which case it will be a commitment endowed with the poetics of hope.

Image: Wes Campbell, “Title Unknown” (Image supplied; no date given).

Some of Wes’s work reminds me of Vincent van Gogh, especially van Gogh’s later work. Here we might think of van Gogh’s Irises, painted in the final year before his death in 1890 while living at the asylum at Saint Paul-de-Mausole in the south of France. Whatever else the paintings by this tormented soul express, they affirm the vitality of life, the durability of light, the colours of existence. And it is a credit to his courage that such affirmation was possible only by the most costly and creative defiance of which he was capable — to paint the opposite of what he felt inside. It seems that the darker van Gogh’s inner world became, the more he reached for colour to “react against the melancholy”, at least on those days when he could paint at all. His Irises are statements of hope’s defiance of the fear-induced powers and systems of death that mark our world, and that torment our minds and bodies.

Wes’s work suggests an artist so thoroughly committed to the world that he does not shy away from bearing witness to the trauma of creaturely existence alongside the refusal to abandon the world to its violence, nihilism, and despair. Indeed, his work tells of, and elicits, hope — hope that does not bypass or disregard the lived realities of the world, hope born of one who refuses to leave the world to the monstrosities and burdens of its own judgements.

“All theology is political”

Wes Campbell’s paintings sit in continuity with Australia’s great figurative and anti-war artists — from Albert Tucker to John Perceval, Peter Seaton, Eva Orner, Peter Drew, George Gittoes, Richard Lewer, and others, alongside which we might appraise his work. Such appraisal calls also for recognising that, for Wes, human life, in all its dimensions, including its religious ones, is inescapably political in character. Like his pastoral ministry, Wes’s painting is embodied public theology. He once wrote, “All theology is political”, which may be a somewhat strange thing to hear from a former Australian Methodist — a tradition better known, unfortunately, for its wowserism than for its political thought, but a year spent in Sydney at the Central Methodist Mission under the ministry of Alan Walker had exposed him to the message of non-violent protest at the heart of Christian faith.

All theology is political — whether one is protesting against the Vietnam War or nuclear weapons, or for an end to South African Apartheid, or in support of Aboriginal Land Rights, or breaking bread with one’s enemies, or performing hope with acrylic on canvas. Proper theological work, as Wes once put it, is “not intended to look into itself, but must expect to be opened to the world.”

Image: Wes Campbell, “Nativity” (Image supplied; no date given).

Wes’s work, birthed of profound theological instincts shaped over many years of deep wrestling with the stories of Jesus, displays a commitment to Christian discipleship marked by “engagement with the contemporary political theories and conditions of oppression”, and by stubborn witness to the future that the God of liberation promises for creation. Wes’s confidence in this claim is grounded on the wager that the “Jesus who died in the company of all dead victims murdered by the powers” was also raised by God. This makes Christian speech possible — something he learnt from the Swiss theologian Karl Barth and the German theologian Jürgen Moltmann, dialogue with whose work heavily informs Wes’s reading of the world, as well as his painting.

Wes shares Moltmann’s conviction that the resurrection of the dead Jesus is the game changer, although not in a way that ever makes it obvious that the game has in fact changed. It announces judgement upon every status quo, exposing as a lie the myths by which we live. Here too artists have a role to play. As the great American novelist, playwright, and essayist James Baldwin once put it:

Most of us, no matter what we say, are walking in the dark, whistling in the dark. Nobody knows what is going to happen to [them] from one moment to the next, or how one will bear it. This is irreducible. And it’s true of everybody. Now, it is true that the nature of society is to create, among its citizens, an illusion of safety; but it is also absolutely true that the safety is always necessarily an illusion. Artists are here to disturb the peace.

Wes Campbell’s art disturbs illusions of peace precisely by subverting the hollow character of the peace that is so often held out. It does that through an invitation to gaze upon one who has “nothing in his appearance that we should desire him” (Isaiah 53.2) and by suggesting that it is in this one alone that all things are finally healed and made new. For these gifts and more, we are left in Wes’s debt.

Jason Goroncy is Associate Professor of Systematic Theology at Whitley College, the University of Divinity, Melbourne.

Jason Goroncy (PhD, St Andrews) is Associate Professor of Systematic Theology at Whitley College, the University of Divinity. His current research broadly engages questions in public theology, theology and the arts, death, and trauma.

Add comment