This article was published by ABC Religion and Ethics

Among other things, COVID-19 has brought with it an invitation to rethink what we imagine a safe society to be. It has also exposed, again, the failures of unbridled capitalism and the fickleness of so much that we call “living.” And it has brought to the surface significant questions about what it means — existentially, philosophically, practically, morally, economically — to speak of human community. Such conversations are most welcome, and I am grateful for their being brought to the fore.

The Christian community is not immune from such conversations, of course, and most of its leaders are, as far as I can deduce, trying their best to quickly reimagine what faithful witness might look like under these unfamiliar and shifting conditions.

(There are, mind you, those trying to carry on with business as usual, for who knows how long, and who are arguing that suspending or cancelling gathered worship services not only betrays a duty of spiritual care but also signals the church’s capitulation to “the spirit of our age, which regards the prospect of death as the supreme evil to be avoided at all costs.” Others are warning that “it would be extremely dangerous, even in the short term, to accustom the faithful to Mass online. It would amount to wishing for a kind of ‘disincarnation’ of Christ.” It’s difficult to take such voices seriously.)

Such imaginative efforts are a reminder of just how adaptive the church has proven to be over the centuries. (They may also be a reminder of why it’s so important for community leaders to engage in activities that stimulate the imagination — like reading decent novels and, when we return to a more “normal” time, visiting art galleries.) The leaders of these communities are discovering and embracing less familiar ways of keeping their communities connected, and of serving the wider communities of which they are a part, especially those persons within it who are most affected by this pandemic — those suffering from ill health, the poor, the elderly, the victims of domestic violence, the isolated, the unemployed.

Understandably, many churches have moved their public gatherings into various forms of online space. Those of us who belong to such communities, and who can access the technology, can be grateful for such connection.

But, as teachers and many others are quickly learning, it’s never a question of simply doing something familiar and which has been developed in the “real” world and then replicating — or “delivering” — it now through new means. Technology changes things. But what exactly? How does the mediation that technology makes possible change the character of both participation and participant, and how the latter understand the relations between themselves?

These are not new questions; and now might be a good time for some of us to refamiliarise ourselves with the work of someone like Jacques Ellul, and to re-read Aldous Huxley (not to mention Garry Deverell’s important work on “Worship as a Technological Apocalypse”). These have taken on a fresh urgency in the age of the internet, and then again in recent months.

Along with others (see here, and here, and here, and here, and here), I’ve been wondering what it means for Christian communities to celebrate Holy Communion online. Some expressions of the Christian church have long been unequivocal about this:

Virtual reality is no substitute for the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the sacramental reality of the other sacraments, and shared worship in a flesh-and-blood human community. There are no sacraments on the Internet; and even the religious experiences possible there by the grace of God are insufficient apart from real-world interaction with other persons of faith.

Others have called for churches to intentionally abandon this practice for the time being, to embrace “a eucharistic *fast* until the virus has finished its work,” to fast “from communion for the time being and [sit]” with this experience of walking with the shepherd through this “valley of the shadow of death.” Such an abandonment represents a concrete way to confess something basic to Christian faith and so at odds with the spirit of much that the modern world celebrates — namely, “we cannot always have everything we want right away.” (In a similar spirit, others are calling for a deferral even of Easter and of instead using this time to dive “more deeply into Lenten quarantine.”) I have been provoked by such words. And I’m grateful for them.

On one hand, we are living at a time of many losses — the loss of physical proximity not least among them. And while most of us are thankful for the provision of technology that enables us to overcome some of the isolation, there is something about our being embodied creatures that is feeling particularly compromised and under-acknowledged at the moment. Embodied community is, of course, at the uncompromising heart of what Christian community means, lest the experience of “church” be reduced to that of an idea.

Writing some 83 years ago, the German theologian and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer encourages us to reject suggestions that the church-community is only ever an invisible entity. Christ’s body, he insists, “takes up physical space here on earth … Thus the body of Jesus Christ can only be a visible body, or else it is not a body at all.” It is a gift that we can continue to meet as community in online spaces — spaces which themselves represent a different mode of our physicality. But it is simultaneously a confession, is it not, of what we have lost, or of that which is being threatened. To try to carry on with business as usual — like celebrating Holy Communion — might represent a failure to acknowledge that loss.

Conversely, to make a point of not celebrating the Eucharist might be a sign of that inability to meet together — or at least a sign of the additional limitations of the modes under which we currently “gather.” This too seems to be an important feature to name at this time. In this way, delaying celebrating communion really might be an act of hope — the hope of our being rejoined; the hope of truly being able to pass the peace and to pass the cup to one another; the hope of being again the “visible body” that can be bumped into, and which can bump into others.

On the other hand, Bonhoeffer also reminds us that it is only in Christ that “the continuity of [our] existence [is] preserved.” In which case, delaying celebrating the Eucharist (or Easter, for that matter) risks locating the joy of the Eucharist (and of Easter) in a change of our current conditions rather than in the Crucified and Risen one. Perhaps such a risk is worth taking? I don’t know. But in such a context, celebrating the Supper, even with the limitations under which we work, might be a way of embracing this promise that only in Christ is the continuity of our existence preserved. Of course, the Eucharist functions as a sign of this reality, a sign that many of us welcome at such a time of high uncertainty and, for some of us, anxiety. There are, therefore, pastoral reasons why it might be important to eat and drink virtually together.

There are also some theological reasons. Graham Ward encourages us to think about the way that the unstable body of Jesus witnessed to in the Gospels is now, in this time after or during the ascension, “an extendible body.” He suggests that it is not that Jesus “stops being a physical presence. It is more as if this physical presence can expand itself to incorporate other bodies, like bread, and make them extensions of his own.” He continues:

[It is] as if place and space itself is being redefined such that one can be a body here and also there, one can be this kind of body here and that kind of body there. Just as with the transfiguration, the translucency of one body makes visible another hidden body, so too with the eucharist, although in a different way, a hidden nature of being embodied is made manifest. Bodies are not only transfigurable, they are transposable.

(For those who think, as a friend of mine has suggested, that Ward’s logic at this point represents an unintentional but “decidedly gnostic ghost,” one might equally make the same kind of argument by turning to someone like Louis-Marie Chauvet, who insists that while the body of Christ is extendable, such extensions can, as my friend puts it, “only be discerned as the body if they keep the character of Jesus [his words, his patterns and deeds] as they come to us in the primitive kerygma [including the primitive liturgical formulations]. This puts a break on what might count as the body of Christ, especially in the world of the postmodern iteration where even vampires are claimed as symbols of the church.”)

I wonder what this means for communities committed to celebrating Holy Communion during this time of social distancing. Such communities readily confess that Christ can make himself available to us by other means, and some theologians have been speaking for some time about the implications of “digital embodiment.” In which case, celebrating Holy Communion would be a way to bear witness to this Christ who is continually being transfigured. Graham Ward also suggests that Jesus’s body is “continually being displaced so that the figuration of the body is always transposing its identity.” He goes on:

Poised between memory and anticipation, driven by a desire which enfolds it and which it cannot master, the history of the Church’s body is a history of transposed and deferred identities: it incarnates a humanity aspiring to Christ’s own humanity.

I wonder if we are now living during such a time when we are experiencing in other ways such “transposed and deferred identities,” and how continuing to celebrate Holy Communion at this time might bear witness to One in whom alone “the continuity of our existence is preserved.”

Perhaps one way forward would be to celebrate the Eucharist by means of an online platform (such as Zoom), to read together (sic) the liturgy of the Supper, to eat together (sic) food that is available, but to keep our cups which are present empty? There are, of course, some significant problems with this tentative proposal. Theologically, it unavoidably draws further attention, for example, to significant and difficult questions about the character of mediation in our virtual spaces. And for those (say Anglicans and Lutherans) who can’t or won’t imagine an edited version of their liturgies, there will be real questions about what it might mean to consecrate an empty cup (something, by the way, that I am not arguing for).

At this point, many Zwinglians will be wondering what all the fuss is about, and insist that any challenges are mostly technical ones that can be overcome with technical and pragmatic solutions. Pastorally, it may simply be too confusing to depart so radically, and so quickly, from familiar practices, and at a time when we are confused enough. It also assumes that people are “confident about handling the Eucharistic elements at home.” These may well be reasons enough to refrain completely.

Still, practicing something like my tentative proposal now might mean continuing to celebrate this meal as a graced sign of what by faith is true in degrees at all times, but which is experienced now through other modes — both the presence of Christ by the Spirit and the compromised but hopeful orientation of Christ’s body, “until he [or she] comes.” Who knows? And does it really matter anyway?

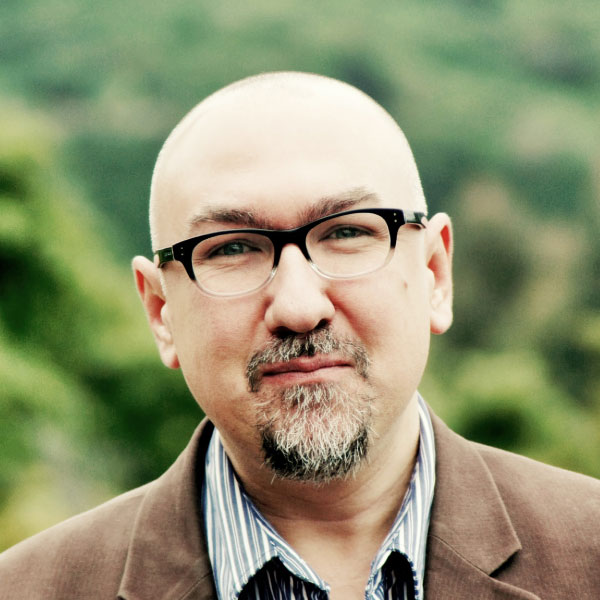

Jason Goroncy (PhD, St Andrews) is Associate Professor of Systematic Theology at Whitley College, the University of Divinity. His current research broadly engages questions in public theology, theology and the arts, death, and trauma.

Add comment