Read the original blog post, published on 5 April 2019, at https://xenizonta.blogspot.com/

Last year I published (through MediaCom) a short commentary on the Uniting Church’s Basis of Union. It has the slightly (but deliberately) long title, “In His Own Strange Way”: A Post-Christendom, Sort-of Commentary on the Basis of Union. The book aims to bring the Basis into conversation with some key contemporary issues.

Last year I published (through MediaCom) a short commentary on the Uniting Church’s Basis of Union. It has the slightly (but deliberately) long title, “In His Own Strange Way”: A Post-Christendom, Sort-of Commentary on the Basis of Union. The book aims to bring the Basis into conversation with some key contemporary issues.

Each section of the book focuses on a particular passage of the Basis by way of a short ‘commentary’ (loosely defined!). This is followed by some discussion starters to locate the text in post-Christendom, a set of specific questions, and finally a passage from the Bible as a suggested focus for developing connections between the Basis and the Bible. The book has been designed to be used for either individual reflection or group study.

In each of this series of four blog posts, the commentary on one selected paragraph from the Basis is reproduced, specifically Paragraphs 1, 5, 10 and 11.

If this whets your appetite, you can order the book through MediaCom or CTM Resourcing. There’s also a short article about the book in the NSW/ACT Synod magazine, Insights.

Commentary on Basis of Union, Paragraph 1.

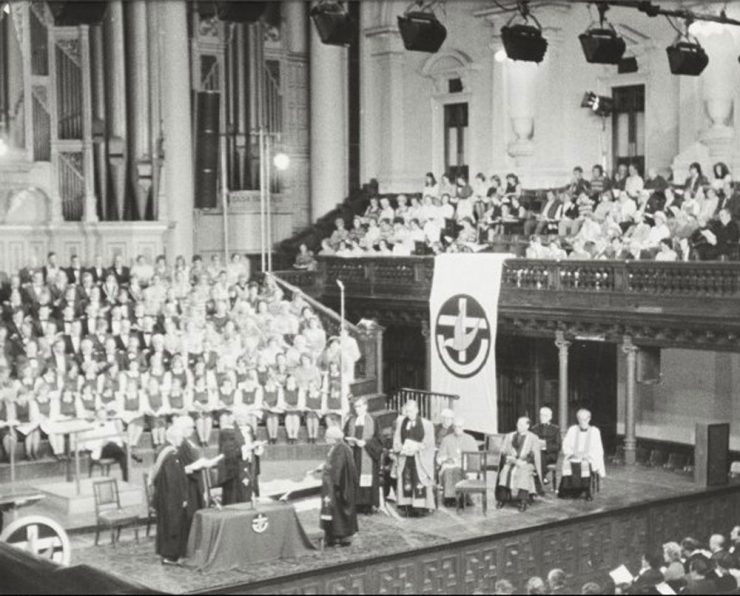

The formation of the Uniting Church on June 22nd 1977 was big news. It was headlined on the front pages of many of the daily newspapers. The inaugural service held in the Sydney Town Hall was replayed on ABC TV that same evening. Indeed, it even claimed international attention. Firebrand preacher, Ian Paisley, not satisfied with the bigotry he was fomenting in his native Northern Ireland, travelled to Sydney to protest about this new ‘ecumenical’ church. More happily, Synod-based services marking the UCA’s advent were held in Australia’s capital cities on the following Sunday. They were packed.

Have we lived up to the expectation? And how would we answer that question in any case? If we used this opening paragraph of the Basis as a criterion, we might ask whether, when we gather in our various communities of faith week by week, we do so acknowledging “one another in love and joy as believers in our Lord Jesus Christ” and in order to “hear anew the commission of the Risen Lord to make disciples of all nations, and daily to seek to obey his will”? Or to lower the register of the language, we might simply ask: Is Jesus Christ and his mission central to our life as Christian communities? This is a much more serious test of the state of the Uniting Church than any narrative about numbers or any data about demographics.

The union of churches that produced the Uniting Church in Australia was not a denominational merger. Its purpose wasn’t to consolidate resources. It wasn’t a strategy of expansion. It wasn’t driven by a vague sense that it was a good idea. No, at least according to this paragraph, union was embedded in some deep theological convictions: it was intended for the glory of God; it was a call to “sole loyalty to Christ”; its horizon was nothing less than the kingdom of God which Jesus had proclaimed and for which Christians hope.

Right at the outset of the document, union is set within a context of the triune God, the centrality of Jesus Christ, the call to mission, and the hope of the coming kingdom. The UCA was not intended as a ‘new Church’ or a new ‘denomination’ – even if that is the language that might come most easily to us to describe what happened. Indeed, it was probably inevitable that this is how the event of union would be described and understood – both within and outside the church. To counter that inevitability, one way of summarising the spirit of this paragraph might go like this: the formation of UCA was simply a new episode in the history of the ‘Church of God’.

The logic at work in this paragraph is precisely the logic that challenges ‘denominationalism’, the phenomenon of Christendom by which the divided Churches defined themselves over and against each other. ‘We are this kind of church.’ ‘We do communion this way, not your way.’ ‘We appoint our ministers this way, differently from you.’ ‘We have this form of government, unlike yours.’ Of course, Christianity has never been homogeneous: it has always displayed variety and diversity. But denominationalism turns that variety and diversity into division. It makes primary, things which should be secondary: forms of government and leadership; modes of worship; theologies of ordination, or beliefs about the sacraments. For instance, consider the names of the three Churches which entered union: each one of them was known by a title which referred in one way or another to the form of government adopted or to the way it structured Christian experience: Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational. In other words, Christians from these churches identified themselves to each other by the way they organised themselves.

One of the most striking post-Christendom notes in this paragraph is precisely the move away from these denominational labels as markers of identity. They are challenged and subverted by the seemingly innocuous but deeply challenging summons: “In this union, these churches commit their members to acknowledge one another in love and joy as believers in our Lord Jesus Christ.” As noted above, this union was not simply an organisational merger. It was an event that called forth a deeply personal response from the individual members of each of the denominations. No longer would Presbyterians, Methodists and Congregationalists identify themselves or one another in those terms. Nor was the challenge from now on simply to recognise one another as fellow members of the Uniting Church. That would simply replace one form of denominationalism with another. No, something even more fundamental was being called for: an acknowledgment of each other as ‘believers in our Lord Jesus Christ’. We might baulk at the language of ‘believers in’ rather than, say, ‘followers of’ Jesus Christ, but the basic point of Christian identity is stated. Christians are Christians through their relationship to Jesus Christ.

Of course, at one level acknowledging fellow Christians as Christians can be a fairly formal or superficial process. Beneath (and not always beneath!) the acknowledgment can be mutual suspicion, hostility or indifference. Here, however, the Basis invites those entering union to set those aside and to accompany the mutual acknowledgment with a key Christian virtue and an equally key Christian disposition: love and joy. This is not about whether we like our fellow Christians or whether we can put up with them. It’s about the hard work of acknowledging that in Christ I am connected and responsible to any other person whom Christ calls into the church and that together we are equally called by Christ into his mission.

*****

The three remaining posts in this series will be published in due course.

Add comment