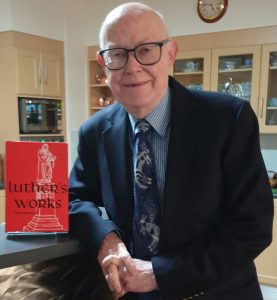

August 2020 saw the release of a significant volume in the American Edition of Luther’s Works, the definitive English language translation of Luther’s writings. Volume 73 (LW 73) is the first of two volumes devoted to Luther’s academic disputations. Almost half of this volume comprises the introduction and translation of his Antinomian Disputations (1537–1540) by Jeffrey Silcock, lecturer emeritus in systematic theology at Australian Lutheran College. His interest in these disputations, originally written in Latin, had its beginnings in his own doctoral dissertation in the USA in the mid-1990s. He now plans to write the book that was never written, which will evaluate Luther’s role in the first antinomian controversy in sixteenth-century Germany.

The Antinomian Disputations, held at the University of Wittenberg, and presided over by Luther himself, were the culmination of a protracted debate between Johann Agricola, a pastor and former student of Luther who had turned antinomian, and Luther’s co-worker Philip Melanchthon. At stake was the question of the role of the law in repentance. Agricola argued that it was the gospel and not the law that brought about contrition, while Luther and his colleagues held that it was primarily the law and not the gospel that was meant to bring about contrition. While at first sight, this might sound like a debate over semantics, Luther considered the matter so serious that he eventually entered the fray himself in its final years and argued that, among other things, if the law or Decalogue were abolished from the church—which was exactly what the antinomians were intent on doing (antinomians being those who rejected the place of God’s law in the Christian life and replaced it with the gospel and the Spirit)—then the gospel itself would be at risk of being lost. So if you are puzzled by that and want to know how it happens, you’ll have to read the book!

In a nutshell, Luther argues that it is the task of the law to first expose our sin and to bring us to the point where we realise our need for the gospel and its message of forgiveness through faith in Christ. Luther appeals to Jesus’ words in support of his law–gospel sequence: that those who are well have no need of a physician, but sick people do (Mark 2:17). In other words, unless the law first makes us aware that we are spiritually sick on account of sin, we will be unaware of our need for healing and forgiveness, which is brought about by the gospel. And if we use the gospel to do the law’s work instead, which is possible, the result will be that we end up turning the gospel into law and so effectively losing the gospel.

Although the debate was often conducted in learned disputations at the university, Luther maintained that the issues involved were at the centre of preaching and pastoral care. In fact, he held the evangelical pastor at Halle, who was an antinomian, responsible for the suicide of Dr Krause who came to him for help because he was overwhelmed by guilt due to his denial of Christ. This man, a senior official of the well-known Archbishop Albrecht, had received the Lord’s Supper in both kinds when the Reformation first began to take hold in Halle; at the time, the archbishop was out of town. When he returned and opposed the attempted reforms, Krause stood back and denied the gospel. The fact that others willingly accepted suffering and banishment, among other things, on account of the evangelical faith, not only shamed him but drove him to such despair that he could no longer take comfort from the gospel and ended up taking his own life on All Saints’ Day, 1527.

In Luther’s opinion, the problem was that the pastor did not first examine the penitent’s conscience in the light of God’s law but immediately proclaimed the gospel to him, reassuring him of God’s love and forgiveness. However, Dr Krause came back and told him that he could not believe that God had forgiven him that easily, because he was too great a sinner. But the pastor had shot his bolt. He had used his best and most powerful weapon against despair first, the gospel, and now he had nothing more to offer him. The man left in despair and not long afterwards took his life by slitting his throat.

Luther, on the other hand, based his approach to pastoral care on the model exemplified in the story of David and Nathan in 2 Samuel 12. David came to Nathan the prophet with a guilty conscience after committing adultery and then murder to cover his tracks. However, Nathan did not immediately proclaim God’s mercy and forgiveness. He did not start by telling David that he had nothing to worry about because God was gracious and merciful. No. First, Nathan confronted him with his sin. He cleverly told him a story by which he could hold up to him the mirror of God’s law without him even realising it. It ended, as we know, with David condemning himself out of his own mouth. He confessed: I have sinned. Then Nathan in turn announced to David: And God has put away your sin, you are forgiven. This is the law–gospel model of pastoral care that goes to the heart of Luther’s theology. And it is precisely this proper distinction between law and gospel that lies at the centre of the Antinomian Disputations.

These disputations in LW 73, which also include seven doctoral disputations on various topics, are a masterful piece of scholarship and show Luther at his most astute. But as the above example shows, they are not merely an exercise in rigorous theological argument for their own sake, but for the sake of the gospel and therefore these disputations have important implications for preaching and pastoral care. It is precisely this inseparability of doctrine and practice that is the hallmark of all good theology, not least the theology of the Reformation tradition.

Luther’s Works, American Edition, is published by Concordia Publishing House, (St Louis Missouri).

Australian Lutheran College is a college of the University of Divinity from the Lutheran tradition, based in Adelaide, South Australia.

Add comment