My wife had just dropped off our kids at the local Coptic Orthodox Church we attend in Cairo and sat down with her Egyptian friend at the adjacent church-owned cafe. After initial pleasantries, she spoke of this current article I was then researching.

“Oh, do Americans have Sunday School also?” inquired the mother. “I never knew.”

My wife and I have lived in Egypt for nearly nine years and consider ourselves of evangelical faith. But we wish also to learn about ancient Christianity and, to the degree possible, worship within the Coptic Orthodox Church, which many Protestants here respectfully call “the mother church.”

We have been impressed by their biblical fluency. We have marveled at their forgiveness after martyrdom. But to entrust our own children to them?

We have been blown away by their care for the next generation. It takes two years of training to even teach a kindergartener.

It was not always so, and they have the Americans to thank—sort of.

Foreign Influence

The modern Sunday school movement began in late 18th-century Britain and spread quickly to the United States. In 1825, the UK Church Missionary Society arrived in Egypt, and American Presbyterians followed in 1854. Both immediately began distributing children’s literature, working alongside the population at large—Muslims particularly.

Neither group had much success, and they adopted different attitudes toward the Copts.

The English missionaries sought to work alongside what they considered to be a sisterly episcopal body unaffiliated with Catholic Rome. Coptic papal permission was given to establish a seminary in 1843 to train Orthodox priests in their parish ministry. At that time, clerical roles were mostly inherited within families, with no formal training beyond rites and rituals.

The seminary closed five years later, unable to cross-pollinate amid considerable suspicion.

The Americans opened schools. Still a new idea in Egypt, they were of vastly better quality than the few local options, especially in Upper Egypt. Presbyterians trace their seminary in Cairo, now over 150 years old, to a boat purchased to sail up and down the Nile River.

As they attracted Coptic converts, the missionaries established congregations, and the Sunday schools proved popular. In 1870 there were around 200 Egyptian children attending; seven years later, more than four thousand.

It was a dire moment for the Copts. Authorities granting equality with Muslims a generation earlier also allowed entry of competing versions of Christianity, preached by foreigners with financial means and modern education.

The Coptic Pope Kyrillos (Cyril) IV (1854–1861) became known as the “Father of Reform” for welcoming Western innovations. He opened the Great Coptic School and imported a printing press. But his successor, Demetrious II, gave far less attention to education, instead threatening excommunication for families sending their children to missionary schools.

Popes would alternate between reform and reversal, but all were trying to undo a situation of inherited darkness.

Looking backward eight decades, the beloved Pope Shenouda III, known as “the teacher of generations,” described the solution with primordial imagery. “Our teacher … started his life in an age that was almost void of religious education and knowledge,” said the patriarch, who died in 2012. “Then, God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light. And the light was Habib Girgis.”

Coptic Educator Extraordinaire

Girgis was born into a middle-class family in Cairo in 1876. One of four children, his father died when he was only six years old. Even so, young Habib was fortunate to be educated in the Great Cairo School.

In 1893, Pope Kyrillos V (1874–1927) resumed his namesake’s reforms and opened the Clerical College, the first Coptic theological institution since the patristic-era School of Alexandria. Girgis was one of 40 students chosen to be part of the first class. Unfortunately, he discovered that almost none of the instructors had any training in theological education. The dean simply read aloud from religious materials.

Girgis lamented the situation. “Is there among us anyone who is capable of responding to those who ask him about his religion and why he is a Christian?” he asked in a student lecture four years later. “I am sure that most of us do not have an answer, except to say that we were born from Christian parents and hence we are Christians.”

To a large degree, Girgis had to educate himself. He read Tacitus, Tertullian, Justin Martyr, and Clement of Rome. Even before graduating in 1898, he was appointed as a theology professor. Twenty years later, in 1918, he would be named dean of the Clerical College, a position he held for the rest of his life. In the intervening time, Girgis began the most transformative change in Coptic education since the patristic era: the Sunday school movement.

Sunday School Is in Session

Girgis remained celibate his entire life and poured himself into a ministry he created almost entirely on his own. A faithful Orthodox Christian and archdeacon in the church, he mingled with the missionaries who offered their materials and Arabic Bibles. But he wrote his own four-volume catechism to adapt their methods to Coptic distinctives.

Girgis began children’s Bible studies in his central Cairo neighborhood of Fagallah and slowly branched out. In 1900 he went to Upper Egypt for the first time, to spread his ideas there. He established lay societies to promote education and social services. And in 1904 he self-funded publication of The Vine, the first Coptic journal in centuries, to revive patristic studies.

In 1907 Pope Kyrillos V endorsed Girgis’s efforts, writing a letter of support to the emerging Sunday school teacher community. A year later, the pope convinced state authorities to allow Christian religion in the public school system, five years before education became compulsory for all.

But within the church it was more difficult. Coptic Egypt was experiencing the rise of an educated, lay elite, threatening the traditional leadership of priests. A later Clerical College professor described Girgis’s generation as full of devious leaders who put up fierce resistance to his reforms.

Girgis’s solution was to ground the Sunday school movement in the church, under their authority. He worked to establish centers in each village, and in 1918 Pope Kyrillos named him to be on the inaugural General Sunday School Committee, formalizing the movement’s ecclesiastical ties. This official adoption was celebrated by the Coptic Orthodox Church this past March, as the 100th anniversary of the movement.

By 1938, 10,000 students were attending Coptic Sunday schools, with additional branches started in Sudan and Ethiopia. The Sunday school explosion was underway, with Girgis a key link between the clerics and laity. He was elected a member of the Lay Community Council three times, navigating leadership struggles and financial constraints. And from his trusted position as a confidant to Pope Kyrillos, the Sunday school began to infiltrate the church.

Lasting Legacy

Girgis naturally organized the movement from his position as dean of the Clerical College. But despite his efforts, even today the Coptic Church does not require its priests to graduate with academic theological training. Many already possess college degrees in their professional fields and quickly learn the rites of the church. They are identified by local priests, having distinguished themselves in service. And for decades—outside ministry to the poor—the Sunday school was all that existed.

In the 1940s, three particular Cairo churches emerged as centers of the movement, each with a different focus. In time, their students become the most powerful bishops surrounding the pope.

The first focused on developing a critical intellect. Bishop Gregorius came to head the newly established Bishopric for High Studies, Coptic Culture, and Scientific Research.

The second focused on social activism. Bishop Samuel, killed in the assassination of Anwar al-Sadat in 1981, came to head the newly established Bishopric for Ecumenical and Social Services.

The third focused on spiritual revival. Bishop Shenouda, who later became the aforementioned, beloved pope, came to head the newly established Bishopric for General Education. He was Girgis’s direct disciple.

But these leaders were not the only ones to continue reforms birthed in the Sunday school movement. Bishop Musa transformed one of Girgis’s earlier societies—the Coptic Youth League—into the newly established Bishopric for Youth. And Matta al-Miskeen led a monastic resurgence that continues today. While priests are free to marry, monks form the celibate, episcopal leadership pool for the Coptic church. Today a university degree is near-universally required of the would-be novice.

Despite his success, Girgis remained frustrated through the end of his life, as his ideas outran the ability of the church to accept them. Still, he could celebrate in 1938 that the seminary produced two bishops, over 200 priests, and dozens of preachers. Bishop-then-Pope Shenouda would go on to help it quadruple these graduates.

But in Sunday schools Girgis directly witnessed the fruit of his labor. And labor it was. A tireless worker, his strength came directly from his vision for God’s will. In 1948 he counted 43,000 students, four times as many as there were ten years earlier.

“I felt a voice calling me from the depth of my heart,” Girgis said. “My soul is ignited, moving to rise up to the duty … for which God created me—for I was created for its sake.”

Girgis died in 1951, and afterward, the Sunday school movement decentralized. Today every diocese, and sometimes even individual churches, organizes its own curriculum and trains its own workers—called “servants” in Arabic. The current Pope Tawadros, who canonized Girgis as a saint in 2013, is working to unify the work once again and further prioritize education.

“The future is bright for Sunday school,” he said in commemoration of the 100th anniversary, “because it is built on a firm foundation.”

Member of Parliament Maryam Azer also paid tribute. “I am so indebted to all the servants in Fagallah, where Habib Girgis began,” she said. “I have left the Sunday school, but the Sunday school has not left me.”

But perhaps the most significant remark about Girgis’s impact came in conversation with the author of the book upon which this essay is primarily based.

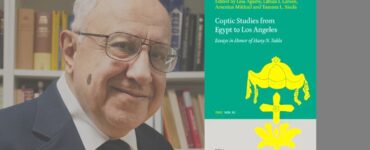

Bishop Suriel of Melbourne grew up in the Coptic Sunday Schools of Australia and did his doctoral research on Habib Girgis. He heads St Athanasius College, which in 2011 became the first theological institute accredited by the Coptic Orthodox Church. He requires all his priests to study for a degree.

When compared to other Christian communities in the Middle East, the Coptic church is unique. Nowhere else is the church as vibrant as we find in Egypt. By contrast, many are torn by war and are rapidly declining.

What is the reason for this Coptic resurgence? Girgis made the difference.

“If he didn’t come onto the scene, would there even be a Coptic church today?” said Suriel. “I don’t know; it is debatable.”

Jayson Casper is the Middle East correspondent for Christianity Today, resident in Cairo since 2009. His website, A Sense of Belonging, chronicles his writings as well as Friday Prayers, a weekly encouragement to seek God’s blessing for Egypt.

This post was originally published by Christianity Today on 20 June 2018.

Primary resources:

Habib Girgis: Coptic Orthodox Educator and a Light in the Darkness, by Bishop Suriel (St. Vladamir’s Seminary Press, 2017)

“Renewal in the Coptic Orthodox Church; Notes of the PhD Thesis of Revd. Dr. Wolfram Reiss,” by Cornelis Hulsman, Arab West Report, Nov. 22, 2002. https://www.arabwestreport.info/en/year-2002/week-46/23-renewal-coptic-orthodox-church-notes-phd-thesis-revd-dr-wolfram-reiss

Habib Girgis: Coptic Orthodox Educator and a Light in the Darkness

Bishop Suriel

This is the first comprehensive work published on the life of Habib Girgis. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Coptic Orthodox Church was in a state of deep vulnerability that tore at the very fabric of Coptic identity. In response, Girgis dedicated his life to advancing religious and theological education.

This is the first comprehensive work published on the life of Habib Girgis. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Coptic Orthodox Church was in a state of deep vulnerability that tore at the very fabric of Coptic identity. In response, Girgis dedicated his life to advancing religious and theological education.

This book follows Girgis’ six-decade-long career as an educator, reformer, dean of a theological college, and pioneer of the Sunday School Movement in Egypt—including his publications and a cache of newly discovered texts from the Coptic Orthodox Archives in Cairo. It traces his agenda for educational reform in the Coptic Church from youth to old age, as well as his work among the villagers of Upper Egypt. It details his struggle to implement his vision of a Coptic identity forged through education, and in the face of a hostile milieu.

Add comment