First published by ABC on 25 Sep 2017

Most political pundits are anticipating that there will be a change of law in Australia to extend marriage legislation to include same-sex couples. It is, they argue, a matter of when rather than if.

If they are right – and I have no reason to disbelieve them – then the arrival of this “when” is cause for both ecstatic jubilation and earnest denunciation.

It is difficult not to suspect that, in a great many cases, such moods are less indicative of moral conviction than they are of a sentimentality that seems to be the only kind of currency – apart from hard cash, and stocks and bonds – available to us under the conditions of late capitalism.

What follows is not about the postal survey currently before the Australian electorate. It is about the way that proposals to change the state’s legislation about marriage occasions the opportunity for both state and religious communities to clarify, and perhaps re-write, certain long-standing arrangements about marriage in Australian society.

I would welcome a change in law, principally for two reasons.

First, because it marks an advance in the cause of equality under the rule of law. I would prefer to live under the authority of a state that was committed to treating all of its citizens equally, even if many advocates of that argument conceive of equality in remarkably abstract terms. It is, so the argument goes, a state’s responsibility to so protect the rights of all its citizens, and to create the space and the legal frameworks wherein competing rights can be navigated without recourse to violence.

The second – and main – reason that I would welcome a change in law is because it would mark a small, but nevertheless significant, retraction of the state’s involvement in a religious practice. (I recognise, of course, and celebrate that marriage is not only a religious practice.)

The belief that marriage is a religious practice – that is, a practice made possible by particular communities that are organised around a shared set of beliefs about the way that the world is – is not uncontroversial, not least among certain kinds of believers who, well-schooled in the abstract logic of late-modernism, think that marriage works independently of concrete religious communities with particular theological or metaphysical commitments, and therefore, that the state ought to have some say here. Marriage is the same thing, whether you tick the box on the census that says “Judaism” or “Jedi” or “Sunni Muslim” or “Oriental Orthodox” or “Baptist” or “No religion,” and the state is the one who tells us what that thing actually is. (That Australian Baptists have conceded this point is a matter of some embarrassment to me, not least because it represents a confession that Baptists have absolutely nothing to offer on the subject that the state has not already said.)

Similarly, self-confessed libertarians and social “progressives” retain an anxiety about the sort of fully-fledged pluralism that this take on marriage inevitably sponsors, and look to the state to act as a kind of referee. To accept that we live in a pluralistic society made up of communities of various God-botherers and God-ignorers, and so on – all with their own particular ways of practicing, or not practicing, marriage – someone at least needs to keep us all in order, and that someone is the state, even if the state’s interest in the matter is principally bureaucratic: a concern for things like taxation and divorce, or winning elections.

In a preferable scenario, the state would have nothing to say about defining marriage at all – it would simply recognise what is actually the case: that both couples and particular (religious) communities have been practicing marriage for hundreds, in many cases thousands, of years before the invention of the modern state, and will continue to do so for as long as we can imagine.

Were the state to recognise that it does not have the ability to sustain the practice of marriage, and that it is unable to provide any meaningful account of what makes a marriage a marriage, this would leave it to get on with doing things that it actually does better – like deciding with whom to go to war, or on whom to spy, or ensuring that our legal, social and physical infrastructures are adequately funded. It would be a win-win for everyone (unless you happen to be an Iraqi child or an Afghani mistaken for an Al Qa’eda operative). The state is good at killing and – the Americans have at last admitted – torturing people. It’s not good at marriage.

But given that for complicated historical reasons the state has happened to find itself in the marriage game, I am prepared to settle for second-best – that is, that the state defines marriage in such broad terms as effectively to rule itself out as an arbitrator of the meaning of marriage.

The New Zealand poet James K. Baxter was onto something important when he observed that “there are many marriages, true though incomplete, which the Church has never blessed or the State ratified.” It is incumbent upon religious and other communities to do their own hard work about marriage and about which arrangements they choose to promote, to witness, and to bless; and it is up to the state to decide which of those arrangements it will recognise and which it won’t. It is proper that the wider society recognise the creation of a “new sociological unit” that a couple has created and “makes possible their special life.”

It is equally proper, as Karl Barth noted, that the married ought to be prepared to make a “public confession of their marriage and desire public confirmation of it.” It is not the churches’ role to “marry” anybody, but simply to recognise and to bless those that God has joined together; this may include acting as a witness to whether the arrangement is indeed consensual.

Neither does the state “marry” anybody. Rather, it merely recognises – or does not recognise – certain arrangements into which people have freely entered. This is not to abandon the idea that both religious communities and the state play an important role in this domestic and social institution, but those roles are not the same. Neither are they transferable.

As a clergy person, I welcome any legislation that encourages a less muddled distinction between law and pastoral care, and between law and prophecy (marriage is both, but not in the same way). The current arrangements are blurred “beyond the border line of what is justifiable in the Christian community” (Karl Barth). Australia might do well to follow the European practice of making a clear distinction between religious and civil marriages.

But where exactly does this leave the question of same-sex marriage within the particular religious communities to which I belong? Here I would like to suggest something to my Christian sisters and brothers who support a change in the law on the grounds of broader social equality, but remain unsure about whether same-sex couples ought to be married in a context of, and with the full blessing of, a community of faith.

Certain aspects of the traditionally-Christian conception of marriage need, I think, to be reconsidered, not on account of fluid conceptions of sex in the wider culture, but in light of the Christian doctrine of God.

In the past, Christians have claimed that sexual union between members of the opposite sex can provide us with a picture – admittedly, a rather weird one – of the triune God. Sex, it is argued, is – or at least has the potential to be – about a mutually self-giving love that stands against the social reality of self-interest. That’s why Christian participation in capitalism is heretical, as is the reduction of sex to self-interest. The gender of self-giving love is beside the point. But the exclusiveness of self-giving love in marriage is also deeply problematic.

Christians have also, at times, claimed that that union is – or ought to be – directed towards the begetting of children. But if there is something to such claims, and I think there is, we need to remember another thing that the Christian tradition has insisted upon: that all of our pictures of God are liable to distortion, and are, in fact, constantly in need of correction. It is here that those in committed same-sex relationships might just be able to help the Christian community sail less closely to the rocks of making an idol of heterosexual relationships.

As many conservative commentators have pointed out in criticism of same-sex marriage, homosexual love is, biologically speaking, non-productive. But it is precisely this feature of homosexuality that might get us nearer to the heart of a Christian understanding of the love of God than do a great many of more conservative accounts of Christian marriage. At the very least, it offers us a corrective against the tendencies of the latter to collapse into a crude form of utilitarianism.

We are, all of us, utilitarians now. Almost everything we do, we do in order to get something else. Such is the insatiable logic of late-capitalism that gets into our bones. This logic represents the antithesis of Christian truth – that God created the world, not in order to get something, but simply for the sheer love of it. Although certain tribes of Christian like to espouse the fiction of a “purpose-driven life” – and why not, for there are riches to be had selling that stuff – these have in fact departed from what the Church’s own Scriptures teach: that the existence of the world is utterly pointless. After all, what could God possibly get from anyone or anything that God does not already have, and have in abundance? What, to put it another way, do we have that we could give to God that is not already God’s gift to us? Before Christians talk about being “fruitful,” they first affirm that everything is already fundamentally good, before they have even got to it.

Many among us spend so much time doing things that are good for something else that we need to relearn that the world, and all that is in it – including ourselves – is fundamentally good for nothing. Christians have sex because it is a good thing to do, not because they are able to produce children. And if they do try to have children, they can do so because it is simply a good thing to make something as pointless as a child, not because they are following the dictates of biological necessity, even where there is an expression of a deep need to have children and not to express a random gratuity.

It is, in the end however, the utterly gratuitous love of God – which Christians call “grace” – that enables the world to be itself: simply to exist for no other reason than that it is good for it to do so. In a world obsessed with productivity, those who claim to follow a God who does things just for the love of it need themselves to engage in pointless activities: eating, drinking, sex, sport, binging on Nordic Noir television shows.

And this is where gay and lesbian people might help us all to understand God a bit better than we otherwise might. Not by engaging in sport, but by reminding us that love is simply a good thing in itself.

These suggestions ought not to be taken as knock-down arguments. Christian communions need to do their own hard work in these matters, weighing up the theological, pastoral and ecumenical implications of their positions – positions best understood as always provisional in nature. Certainly, there are some good theological and pastoral reasons why it might be best to move slowly here. But whatever the churches decide, my plea is that they do so solely on explicitly theological grounds, resisting all other kinds of logic – that of an abstract notion of equality as much as the logic of biological necessity, for example.

To my mind, the pressing moral issue that is of importance to the church is the extent to which particular human actions really are splintered reflections of the divine glory. That’s the sort of discussion we urgently need in the church, and that’s what I am trying to provoke here.

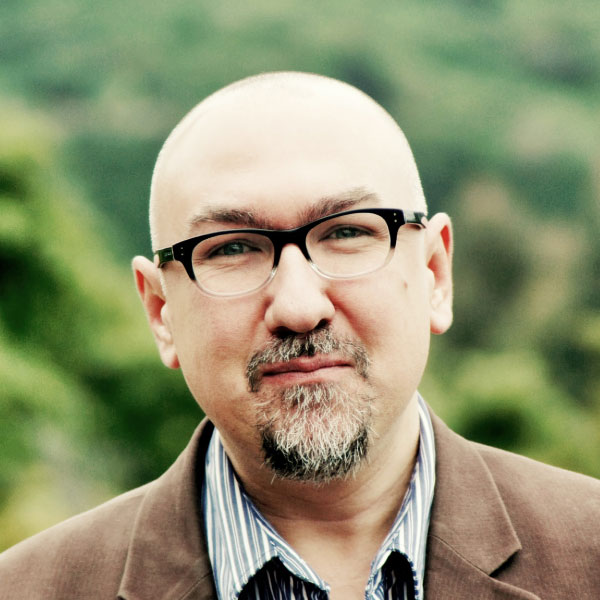

Jason Goroncy (PhD, St Andrews) is Associate Professor of Systematic Theology at Whitley College, the University of Divinity. His current research broadly engages questions in public theology, theology and the arts, death, and trauma.

Add comment